With this in mind, I’ve put this piece together to help people understand who exactly owns the club, and how.

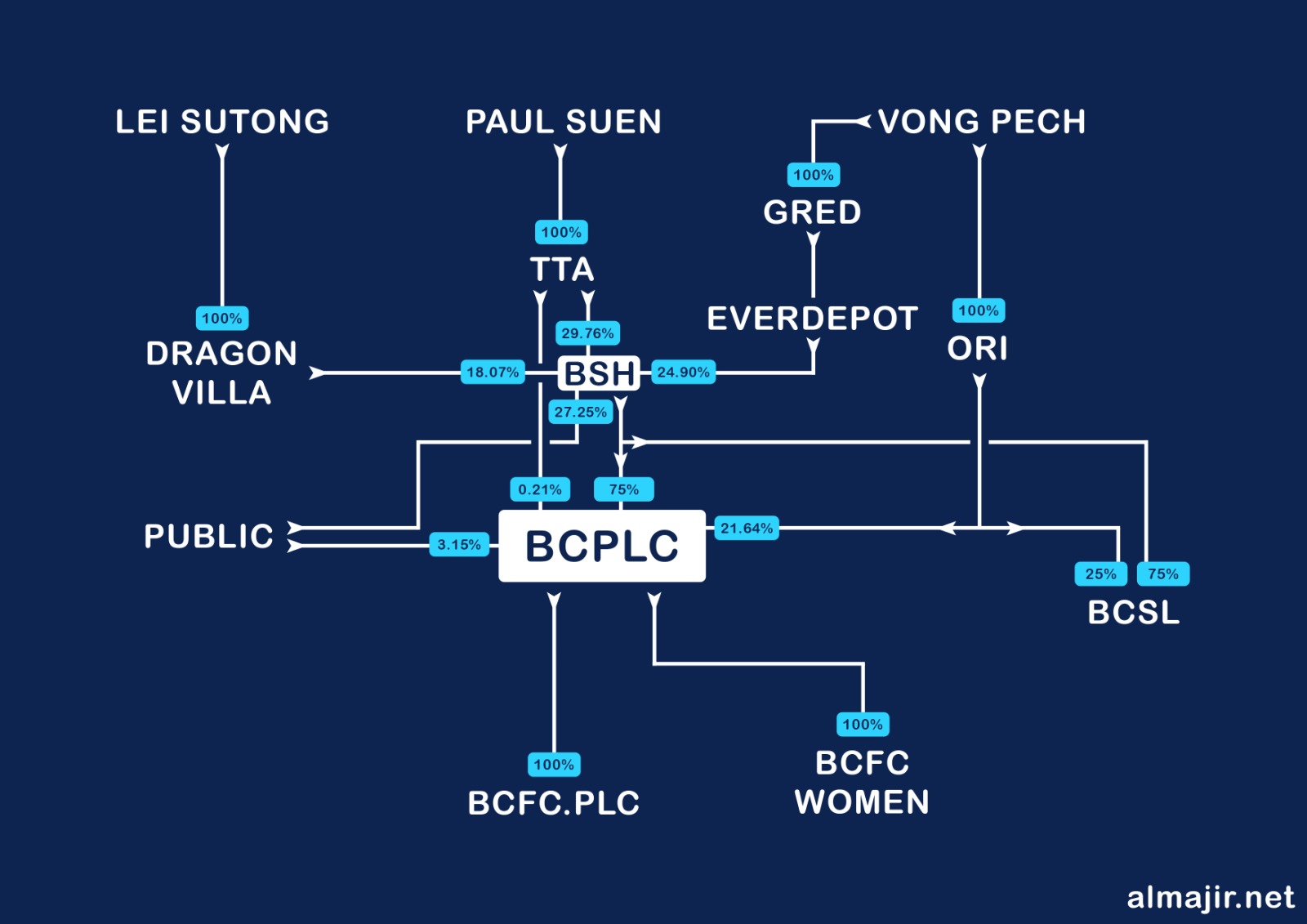

As you can see from the above graphic (kindly put together for me by Chris from We Are Birmingham), the ownership structure looks like Spaghetti Junction. If you click or tap on the picture you’ll get a much bigger version.

How did TTA get involved?

To help understand who owns Blues now, I think it’s important to start from the fall of Carson Yeung and what Ernst and Young (EY) did when they were called in.

Let’s start by rewinding time back to December 2014. Yeung and Peter Pannu are still involved with the club, but they are clinging on to power. Trading in shares of Birmingham International Holdings (as it was known then) was suspended, following some outlandish insider trading stuff Pannu had posted online.

In the boardroom, there was civil war. On the one side was Pannu and his cronies, ready to do Yeung’s bidding, and on the other side was Panos Pavlakis among others, who were against Pannu.

Yeung did everything he could to shift Pavlakis, without success. However, the fight couldn’t continue without something serious happening to the company, and the Pavlakis faction went to the high court to ask for Receivers to be appointed.

One of the key misconceptions is why Ernst and Young got involved.

EY were brought in to look after the minority shareholders in BSH – members of the public who owned small numbers of shares who would be impacted by the fight and had no other recourse to action.

Thus everything EY did was for the benefit of those shareholders. When they advertised for bidders, only one bidder made a bid for the holding company rather than the club – and as that bid was the best one for the minor shareholders, it was the one that EY was always going to accept.

That bid came from Trillion Trophy Asia – the investment vehicle run by Paul Suen Cho Hung.

Yeung did everything he could to stop the deal going through.

Some of this is reported in a High Court Judgement (HCMP 395/2015) which can be found online on the Hong Kong Judiciary website.

The judge noted that BIH was in a “parlous state” – that the club needed HK$10million per month to run and BIH only had HK$16million in the bank – and that it was EY’s top priority to rescue the club to maximise and protect the value of BSH.

Yeung had other ideas. His legal team submitted 24 pages of documents, outlining every conceivable legal argument possible to delay and oppose EY’s work.

To enable the club to keep functioning, EY had agreed a period of exclusivity with Trillion Trophy Asia; this had then ensured TTA had made a loan facility available of HK$153M to keep the company functioning along with cash collateral of HK$9.8M.

Yeung objected to this, saying he could bring online other investors, but failed to furnish any concrete info of who these might be when EY asked.

The High Court eventually threw out Yeung’s complaints, and EY completed the task of pushing him out and bringing TTA in.

Shares were relisted, and TTA officially became the majority shareholder of the club in October 2016. This was the start of the process to where we have got to now.

How did the Vong Pech, Dragon Villa and the rest get involved?

Although it was Suen who rescued BIH (and thus the football club) by loaning money, it’s absolutely essential to remember that Suen was never interested in the football club.

Suen’s modus operandi has always been to buy distressed listings, sort them out and flip them on to another party. While Suen was happy to put money in to get a resumption in trading of the shares of BSH, he was never going to be the person to put in money in the long term.

In 2017, BSH took out loans with two third party companies – Dragon Villa and Chigwell Holdings. Dragon Villa lent the company HK$100M in August 2017 while Chigwell Holdings lent HK$150M in October 2017. These loans were made in the form of “revolving loan facilities”; essentially like having a bank account with these companies with a maximum withdrawal limit, which could be paid back at any time.

That money got burned through quickly.

By December of 2017, HK$70M had been used of the Chigwell money while the Dragon Villa facility was maxed out. This was troublesome for BSH, as they needed more money but couldn’t pay these facilities off.

The answer they came up with was to swap debt for equity. Rather than paying off the loans with cash, they gave the loaning companies shares to the same value, with the base share price “discounted” so that both companies got more shares than they would through the market. In creating these shares, they diluted the ownership of other shareholders, meaning TTA had a little bit less control of the company.

Chigwell were given 500M shares in BSH, while Dragon Villa were given 714.286M shares. These numbers meant both companies became substantial shareholders, and had to disclose their owners to the HKSE.

However, the money worries for BSH didn’t stop.

In March 2018, Dragon Villa made another loan facility available to BSH so that the company had cash to keep itself running. By June 2018, BSH owed Dragon Villa another HK$144.9M and BSH had to create another 1.380Bn shares to pay them off. This made Dragon Villa the second largest shareholder at the time, and once again diluted everyone else’s percentage shareholding.

In the meantime, BSH were also trying to diversify their interests to satisfy the HKSE that it was a viable company.

To do this, BSH looked to invest in a building project in Phnom Penh, Cambodia called One Park. Of course, BSH couldn’t afford to pay for this investment with money, so instead they offered a huge stake – 24.90% – in BSH as payment. The company who would receive the shares was called Graticity Real Estate Development Ltd (GRED), which is 100% owned by Chinese-Cambodian businessman Vong Pech.

This deal took five months and the approval of shareholders to complete, with final documentation signed off in November 2017.

A year later, a deal was done for another section of the One Park property, this time for another 832M shares. Again, this altered the make-up of the ownership structure, and once again diluted other people’s shareholding – including Paul Suen.

This is all so confusing. What does any of this mean?

If you’ve got this far and you’re confused, then don’t worry. It is confusing, and probably deliberately so.

By involving so many other companies, it makes it harder for the casual investor (or in our case, fan of the club) to understand who owns what and who is in control. More importantly, by creating so many extra shares, it makes it impossible for an outsider to come in and take control of the company.

To illustrate this, let’s look at what is called stock market capitalisation.

Stock market capitalisation is the easiest way to calculate the value for a listed company. The calculation is simple – take the total number of shares and multiply it by the share price.

We can use disclosures filed with the HKSE to find the relevant figures.

When Paul Suen took control in October 2016, there were 5,393,764,429 shares in BSH in circulation. Taking the price Suen paid in this transaction of HK$0.08, the stock market capitalisation of the company was 5,393,764,429 x 0.08 = HK$431,501,154 – which works out to be about £43M or so.

Right now, thanks to all the dilutions and share subscriptions there are currently 18,226,422,508 shares available in BSH.

At the closing price on Thursday of HK$0.16, this means that the company is valued at 18,226,422,508 x HK$0.16 = HK$2,916,227,601, or about £277.54M.

In October 2016, Suen owned 70.92% of BSH. The value of this shareholding is easy to work out – simply multiply the stock market capitalisation by the percentage owned. This gives us the calculation of HK$431,501,154 x 0.7092 = HK$306,020,618

Right now, despite owning 1.6Bn more shares Suen is down to a 29.75% shareholding of the company because of all the extra shares that have been issued.

Using the same calculation this shareholding is worth HK$2,916,277,601 x 0.2975 = HK$867,592,586.298

Despite having had to lend the club money initially and having to spend HK$80million to buy shares as his percentage was diluted, Suen’s shareholding is now worth more than double as much as it was when he started.

This fact on its own should explain why Suen got involved.

Similarly, Dragon Villa accepted 714M shares in exchange for HK$100M of debt in December 2017, and 1.380bn shares for HK$149.4M of debt in June 2018 before paying HK$60million for 1.2bn shares in a rights issue in April 2019. This gives a total investment of HK$309.4M.

Dragon Villa currently owns 18.07% of BSH, which works out to HK$526,962.327 – a profit of a cool HK$217million.

GRED took 2.086bn shares in November 2017, in return for BSH’s stake in One Park, at a value of HK$313,047,374.81, and then a further 832.61M shares for the second section BSH bought at a value of HK$78,873,145.30 before paying HK$81M for 1.62Bn shares in the April 2019 rights issue. This gives a total investment of HK$472,920,520.11

GRED currently owns 24.90% of BSH, which works out to HK$726,153,122.65 – again, a massive paper profit of over HK$254M.

Much of this paper profit was thanks to the December 2019 subscription offer which allowed these shareholders to buy shares at less than a third of their current value.

I’ll readily agree that realising that paper value for those shares as cold hard cash is another story; however I’m also sure that there are ways to utilise this paper value to obtain collateral for more money.

What this exercise hopefully explains is why it’s so hard for an outsider to get involved in buying into the club, let alone buying it – and why the stock market listing is so damned valuable.

So who is this Oriental Rainbow Investments?

With all the money BSH have borrowed, it was inevitable that they were going to get to a point where they literally can’t borrow any more. Because it’s also increasingly difficult for them to sell new shares in the company, a new way to put money in had to be found to keep the club running and in turn keeping the listing active.

The solution was for BSH to sell a chunk of Birmingham City plc to a third party – who could then put money into the club directly using that investment vehicle. BSH had to find a happy medium between selling a high enough stake to get some money in, versus the HKSE telling them they were going to get kicked off the stock exchange.

Birmingham City plc is the UK parent of the club. It was the company that Sullivan and the Gold Brothers used to own the club and was formerly floated on the Alternate Investment Market of the London Stock Exchange.

Back in 2009 when Grandtop (as BSH were known) bought out the club, they bought 96.64% of shares in BC plc, forcing it to be unlisted from the stock market giving the Hong Kong company total control.

There are still a few public shareholders in BC plc dotted around. About 3.15% of the company is still in the hands of the general public although these shares are now worthless for anything more than sentimental reasons.

As I’ve written in other pieces, BSH sold a 21.64% stake in the company to the British Virgin Islands investment company Oriental Rainbow Investments (ORI), along with a 25% stake in Birmingham City Stadium Ltd, which owns St Andrew’s.

The result of this is now anyone looking to buy the club not only has to somehow get through the HKSE stranglehold, but also to negotiate with another party to get total control of the club and the Stadium.

You’ve not mentioned the elusive Mr King yet. How does he come into this?

If all of that mess wasn’t enough, there is one final piece in the jigsaw.

Wang Yaohui (aka Mr King) isn’t mentioned anywhere on the Stock Exchange or by BCFC, and as such to regulatory bodies such as the EFL he does not exist. Yet Wang has so many obvious connections to the club and to the people who own it, he cannot be ignored.

On this website, I have previously shown links between Wang Yaohui with two of the people behind companies who own the club – Lei Sutong, the owner of Dragon Villa and Vong Pech.

There is zero question in my mind that both Lei and Vong Pech are nothing more than patsies for Wang Yaohui. This means that the stakes owned by Dragon Villa, GRED and ORI are all effectively controlled by Wang.

Nor is there any question that BSH Chairman Zhao Wenqing and BCFC directors Ren Xuandong, Edward Zheng Gannan and Shayne Wang Yao are working on his directions. This means that the day to day running of the club is ultimately in the hands of Wang too.

The sale of a stake in the club to ORI has only reinforced the hold Wang Yaohui has over the club and makes it more difficult for sticky beaks like me to look into how these companies fund the club.

Furthermore, using the market cap calculations above it’s possible that Wang hasn’t lost much money in this venture, despite the money that has been pumped into the club by BSH.

What that shows to me is that the performance on the pitch doesn’t matter as much as the performance of the stock – and while there is money to be made from the broadcast income if Blues made it back to the Premier League, it could be immaterial against what can be made on the listing.

Conclusions

The conclusion isn’t pretty, and I’m sorry that things are this way.

I believe the bald facts are the people who own the club know that the money isn’t going to be made from the club being successful; it’s more a means to an end in owning a stock listing where a small uptick in share price can bring in huge amounts of profit.

I’ve always considered Blues to be a toy for people like Wang Yaohui, and I have to say this view is reinforced now. It’s an ego trip to buy a club, and it’s an ego trip to buy players and to watch them play.

I think many people have thought the value is at St Andrew’s, and that to get their money back the owners would have to strip the club bare and sell for what they can. I believe this is mistaken – the value is very much in the stock listing.

If anyone wanted to buy the club, disrupting the trading and value of the listing would probably be the only way to go about it.

4 thoughts on “BCFC Ownership: A Spaghetti Junction Problem”

Comments are closed.